Presentation of the sample

by Jacopo Crivelli Visconti – “To be Painting”

Whoever follows the painting of Paulo Pasta knows his painting doesn’t operate by leaps or ruptures, but through a silent development, natural, an extent of trials and exercises from one canvas to another, through time. The pleasure of seeing, after a gap of a couple months or years, a new exhibition is comparable to keep up with, somehow, close and with a kind of an assiduous conviviality, the growing up of the children of friends. It might happen, in a distance of months, they still look the same, but step by step it gets more evident that no, they’re not the same. Actually, they’ve already become others.

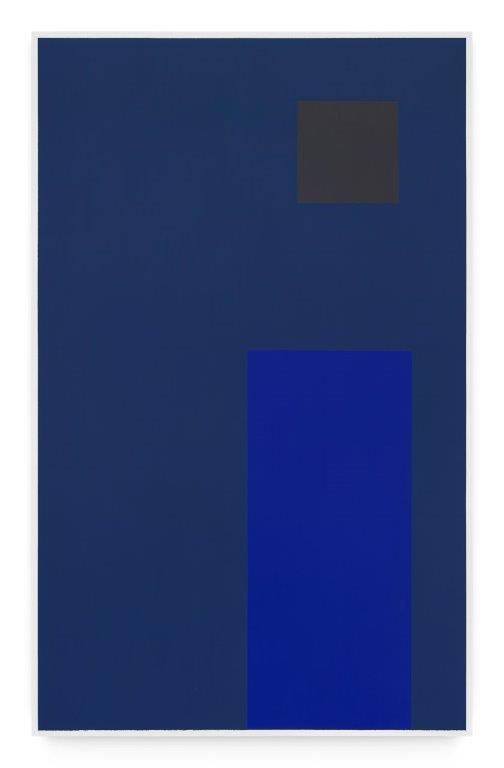

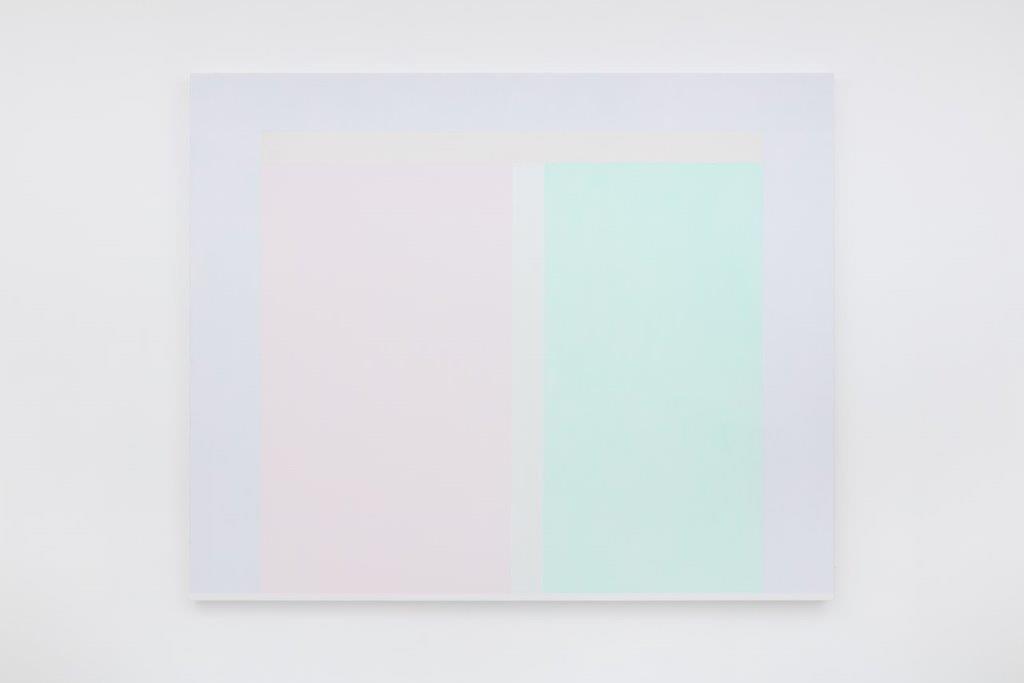

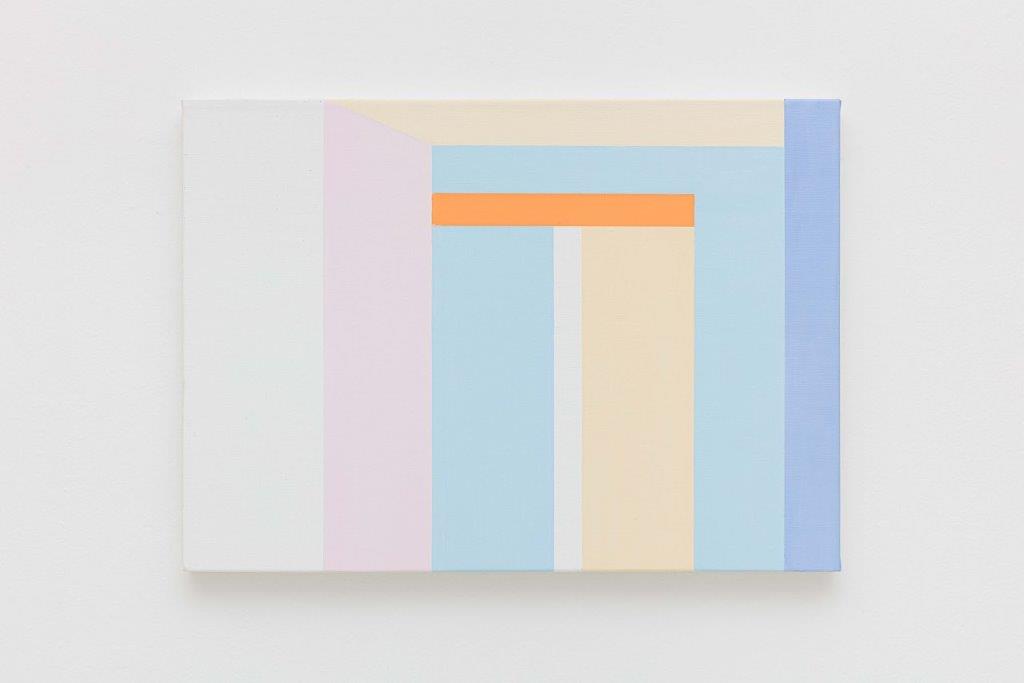

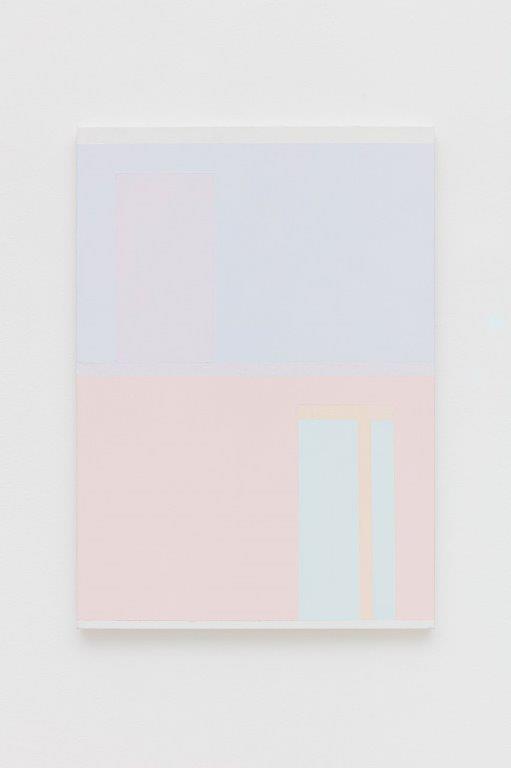

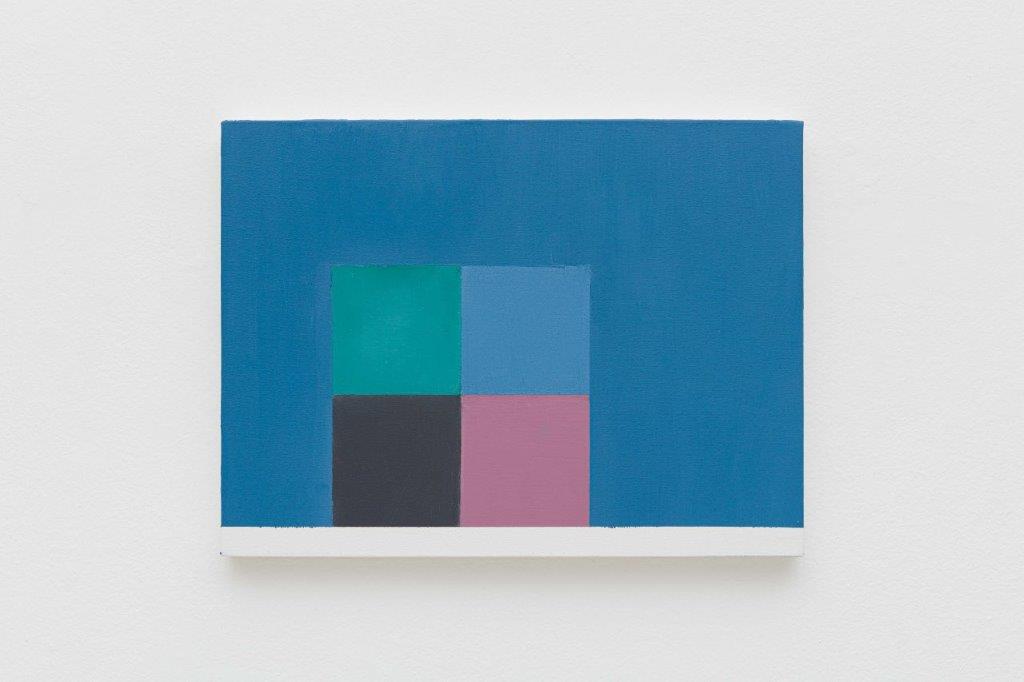

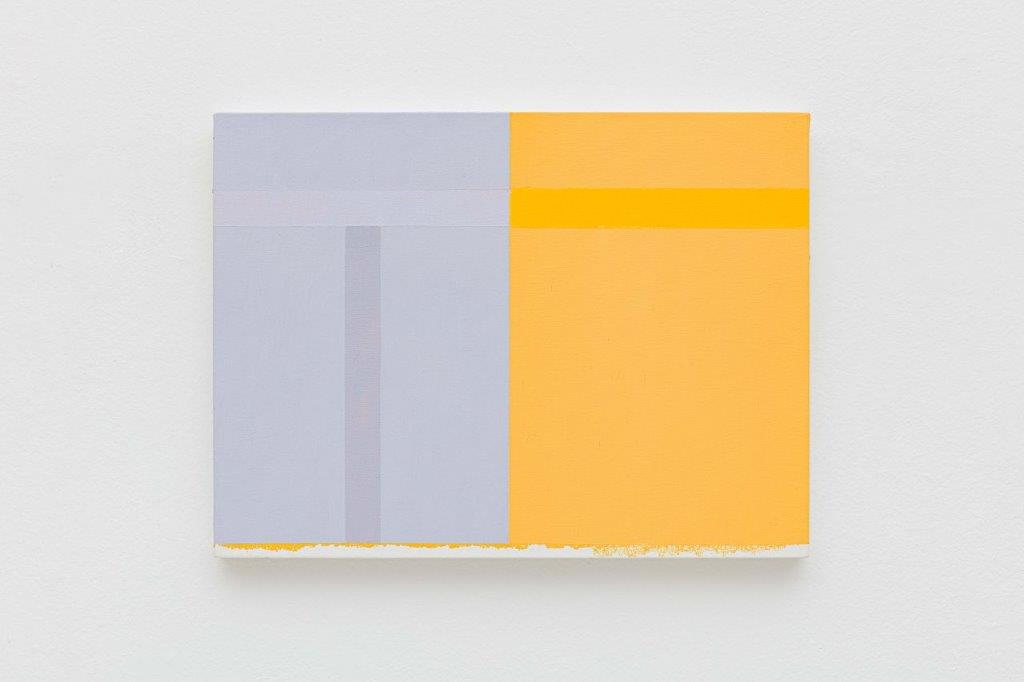

When I got back to Paulo’s atelier, after years since the last time, to see the paintings that would be in this exhibition, the conversation coalesced around the small changes in comparison from one painting to another, or, to be more precise, in the way something in a painting caught the attention and inspired him, that transforms when taken to the other. A particularly subtle line, two rectangles side to side against a homogeneous background, a series of squares that support each other: in front of such a diaphanous and vibratile universe, even things that at first are the same or very alike become completely districts when something around them changes.

The idea that an element might “overshadow” from the painter himself shouldn’t surprise. Regardless of the control over his own composition, as the sharpness of the shapes and variations relatively limited shows in his palette, Paulo is the first one to learn with the result. Because beyond painting, he looks: it takes time to create, and another time to understand. It’s not by chance the artworks are considered finished, many times, days or weeks after receiving the first brushstroke. At this moment Paulo takes off the tape that protects the white strip that usually closes the composition in the bottom.

In one of the most surprising paintings of the exhibition, of which three squares pile up on each other in an apparent unstable balance, when removing the tape Paulo realized that white strip clashed with the rest, then decided to transform it into a pale yellow. What makes the composition unusual is not so much by this detail, but for the presence of the squares. It’s about a shape that also shows up in other paintings of the exhibition, but it’s far from being considered frequent in the artist’s vocabulary. Beyond that, the clumsy way these squares support each other, indicating that the unstable tower which shapes up could tear down at any moment, it suggests a weight, and implicitly, a tridimensionality, absent in most of other artworks.

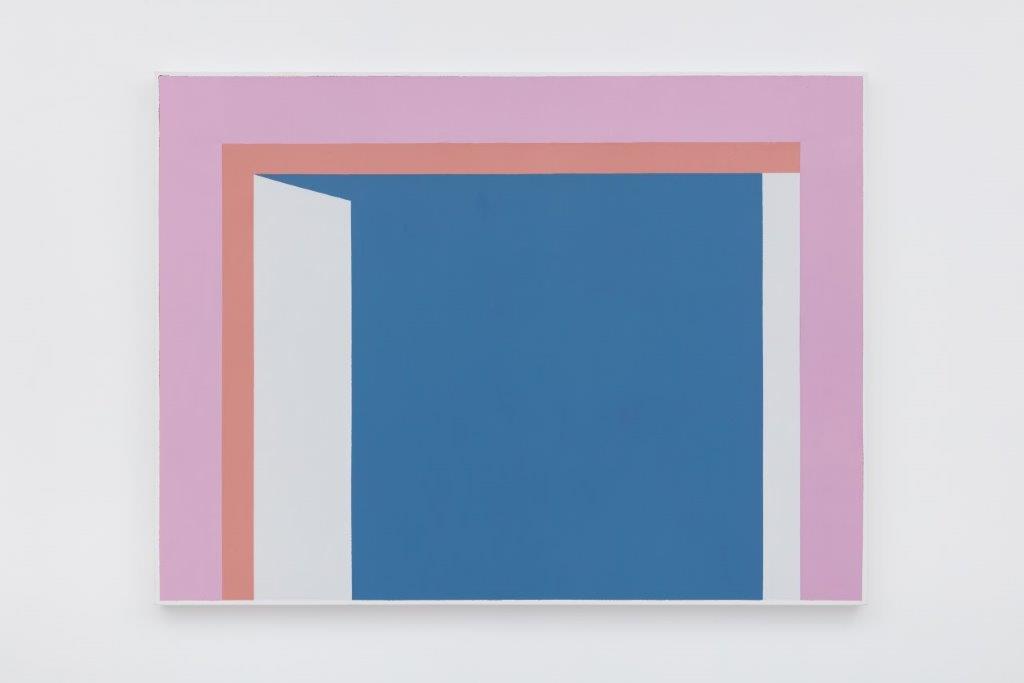

Only another painting of the exhibition suggests something alike when introducing a second element that might be considered rare in Paulo’s poetic: a diagonal line. In this case, the line closes on the top in a white vertical stripe that starts to suggest, thus, what could be a door or a half open window, and again, tridimensionality. But it’s a tridimensionality that has more to do before anything else with the painting history itself: the fact that a diagonal line on a canva can be used to suggest a perspective or a vanishing point. Maybe not by chance, then, that in this canva, instead of a single white stripe on the bottom, Paulo has created a small frame, almost imperceptible, that runs through the four sides of the canva, like a window from which we can watch a scene. But it’s an abstract scene, emptied, where the metaphysical architectures of a Chirico or the colors of a Piero della Francesca became just memories. It’s the idea of a scene.

And an idea, deep down, totally foreign to these paintings, that never tells a story, that never asks to be “understood”, much less in a unique way. Paulo Pasta’s artwork seem to affirm all the time that they are just courts of colors over a flat surface, and whichever architecture or allusion to real world elements that we can read in between them is just that, a reading created by who glances at it, and not something implicit or suggested by the painting. There’s no point in searching in these paintings for a reason for a being or a meaning, but there’s an explanation, or a logic. They only exist, as mountains exist, or a stone, a seawave. This apparent simplicity is in reality the result of a long and coherent reflection, the physical translation of a philosophical thought, of a glare and a deep theoretical and practical knowledge.

The paintings, though, don’t know any of this. They just are, and nothing more.