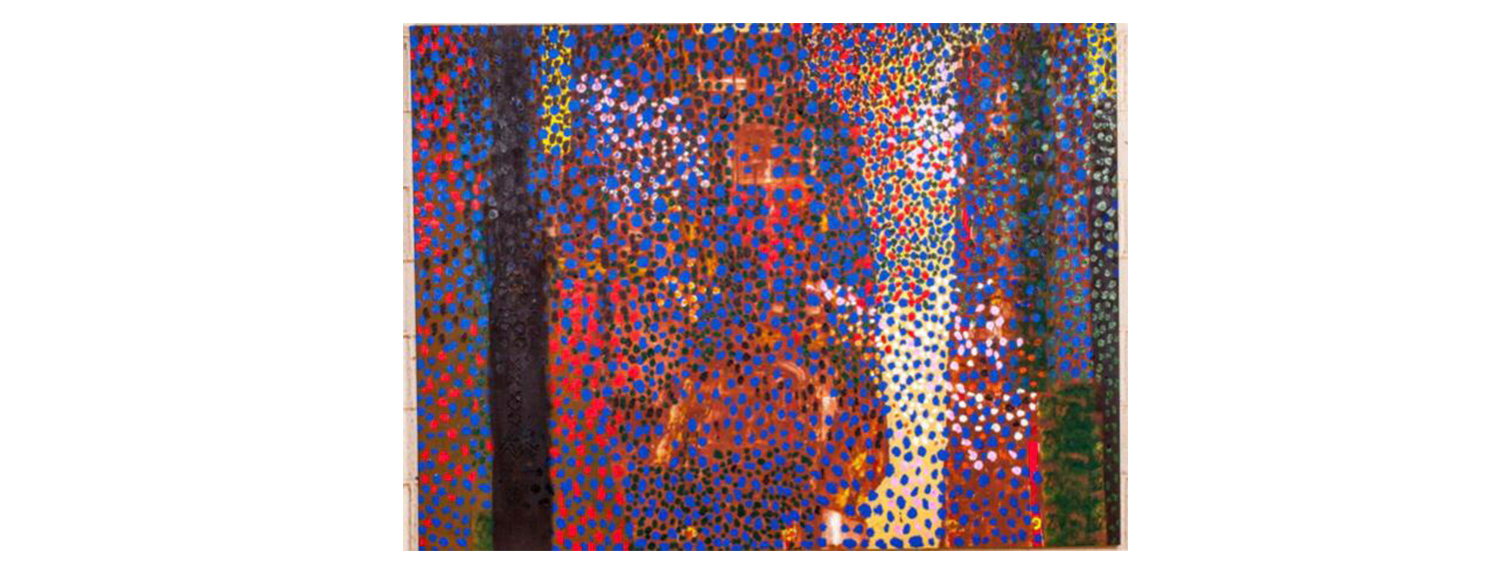

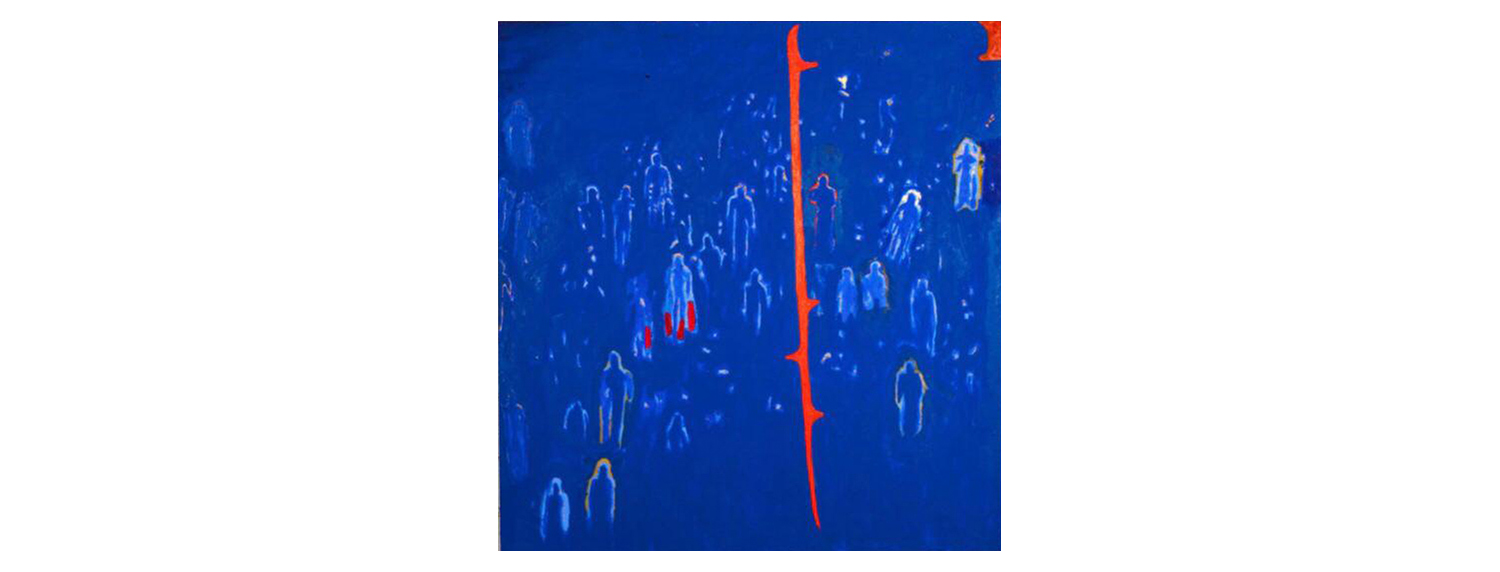

An artwork directly related to a world commitment, the world in which it lives, being realized in its thematic of things seen, lived, invented, and a construction that privileges not only the look, but life, in the very ample sense of man and citizens, their dreams and their nightmares. But like with any other artist, biography is in poetry, in the trajectory of his art, which has in color or in light one generating the other, as life, the revelation of the quest through the variants of a figurativism, today less identifiable at first glance, but regardless, a work born of reality to create a new reality now called art, in its themes of nature, animals and men, vigorous in the inventive capacity to continue producing images while painting.

An intriguing and creative work, primarily as paintings, but also encompassing drawing, illustration, installations, monuments in public places, a diversity of performance and expression which makes him one of the most famous living Brazilian artists for the general audience. All those huge variables seem to come from many lives born of an early talent. At age 12, he attended the Universidade Católica de Goiás in a free course, leaving when he was 17, after sending some drawings for evaluation, without revealing his age. In the 1970’s, he started winning several awards, beginning with the 2nd Bienal de Salvador in 1968, among which he won the Best Brazilian Painter award at the 12th Bienal de São Paulo in 1975. He was born in Goiás Velho, Goiás, in 1947. He has performed his first individual exhibition in 1972, at the Galeria Intercontinental, in Rio de Janeiro. He has being a part several times of the Bienal de São Paulo (Best Brazilian Painter Award in 1974, Prêmio Internacional de Arte Award in 1975) and international biennials in places such as Havana (Cuba) and Medellín (Colombia). Lives in Goiânia, Goiás.

Is your biography in your art? I mean, is everything about you transformed into art, painting, image? Or does the art only re-creates reality?

My encounter with art didn’t occur at a given moment or as a decision, like a task. There was never a moment where I decided becoming an artist. The art, the imagery was born with me, as part of my life, my routine, something inseparable. In fact, there was never an “encounter” either, because we were always together from the start.

In Goiás Velho, my hometown, my parents were volunteers. My mother used to help the church, which was just across the street. It was so close it felt like a part of home. Since I was a child, the linings, the images, the architecture, the altar, everything about that magical world of Catholicism was very close to me. Spending the first eight years of my life in Goiás Velho (when I moved to Goiânia with my parents) was enough time for this chronic contamination. With this came the desire to create, like every child, but in my case this desire never went away. I’m not recreating reality, this is my reality, my biography is my art and my art is my biography.

Using our reality as one of the motivators of your art, which made some people call you an engaged artist, is what takes your attention to other aspects, besides the art itself, such as environment, politics, defense of minorities, etc. Are these matters natural consequences in your artwork or is it created only by the citizen? In short, is your art the fruit of what you are living and has lived or is it a way of discovering the world?

Certainly, my artwork is the fruit of what I lived and am living. I can’t separate my life from my art and vice-versa. Actually, no serious artist can do it. It comes as an amalgam. Some facts motivate me as a human being, and consequently, as an artist. Once my art is my expression, these facts couldn’t be left out of it. Otherwise it would be just illustration or representation.

Although the art is my ground, my driving element, there are many other visual forays in which I have performed, such as trophies, art direction in films, scenography, Quem Paga o Pato? stickers (Gulf War), Lacan posters. I don’t consider them art, it is something else. Coincidentally, these other incursions have to do with the reality, as you mention it yourself. I think I can act in two or more fields at the same time, I feel the desire and excitement to do it, but it has to be taken into account that not everything I do is art; although everything I really like to do is in fact art.

This question of engagement is a mistake, for in this case all great art would be considered “engaged art” and history does not regard it as such. Examples are many: Guernica is certainly the best known, for having been exposed so many times and for having had its image printed on multiple media.

Here in Brazil, during the military period, all artistic production was directed at the lack of freedom of speech. The pop movement itself, which had nothing to do with the military regime as postulated, has been recoded here to express the local situation. The work of Antonio Dias and Cláudio Tozzi are perfect examples of it. I believe no artist on this occasion was indifferent to the military regime, and I am not just talking about the visual artists, but about every artistic class. When it comes about my art, artwork such as O Analista, 1980, O Executivo, 1974, among many others, are in fact works of exposition, however, devoid of the propagandistic aspect.

When the slaughter in Carandiru happened, the artist Nuno Ramos from São Paulo created his “111” artwork. Why isn’t him called engaged? At least when I presented the Césio series, at the Galeria Montessanti Gallery, all income was reverted to the victims from the accident with Caesium – is that the engaged aspect of my work?

Several of your public artwork was destroyed, abandoned, depredated, or have not been preserved, such as the Monumento das Nações Indígenas and Dique em Salvador artwork. How do you feel about public art, not only a “privilege” of yours, being showed this kind of “respect” by the government authorities or the community?

I’m not the only artist exposed to this reality. Personally, I think that, in a country where there are so many homeless children, to be outraged because of it, would be, if nothing else, futile. This abandonment, in Brazil, is not exclusive to public monuments. There are several more serious examples such as the Prophets of Aleijadinho, the churches in Ouro Preto, Goiás Velho. Another unforgettable example would be the wonderful panels of Clovis Graciano in Goiânia, which were simply painted white. And when I think of poorly managed deforestation, unplanned growth, areas that were real forests when I was a kid and used to go for a walk with my father, which are now large residential centers.

And they won’t stop growing. I am not creating a hierarchy for what should or should not be vandalized first. Ideally, everything would be preserved and respected. But if it isn’t, it’s a reflection of the country’s social status. Likewise, I feel entitled to use art to express my outrage. I believe people are entitled to vandalize this very same artwork to express the same outrage as well. It is as if they are finishing my work, or even admitting its existence, by the very fact of destroying it. Amílcar de Castro have never bothered with all the graffiti and urine (which accelerates oxidation) his beautiful iron monuments were vandalized with. He used to see it as the artwork’s “fate”, with other layers in which the artwork would have to be covered with, once exposed in public.

In this approximation with reality, one of your favorite spaces for installations is the Esplanada dos Ministérios, in Brasilia. Some people see this as political opportunism or does the significance of this space for its location effectively become the gain of meaning that you desire when you perform these installations? And yet, fighting for a better world, which is the purpose of these involvements, is worth the disagreements and questions you have to answer for your actions?

Of course it is worth. Otherwise I wouldn’t have done it so many times. And I won’t stop doing them, whenever I feel there is appeal, facts to explore. Regardless of the benefits generated by the change of the federal capital for the Center-West region, Rio de Janeiro was greatly harmed by it. In a way, it turned people away from the central government. Most Brazilians only know what’s going on in Brasilia through television, more precisely, through auditoriums in Brasilia. This distance is definitely not good.

Except for invitations to perform projects within the public art universe (monuments, etc.), my interferences in the Esplanada are my own initiatives and financed with my own resources. Although the best angle is aerial, the topography is perfect, inviting this sort of interference.

Several of them have pictorial content. There are many texts analyzing them as such. In the early 70’s, I performed my first interference work: the Bandeira das Antas. We were at the peak of the military regime. I lost a lot of friends, witnessed to many people suffering. An interesting aspect regarding my Esplanada interferences is that they always went unnoticed by the military. During the military dictatorship time, the use of simulacrum was necessary. They gave me pleasure and motivate my most pure artistic production.

There is other aspect as well. I have a great commitment to the press, which has always supported me, not only by covering my regular interferences but also giving me space to express myself orally. In 1993, I made a crucifix exposing sexual violence. This crucifix was made of vinyl, and on the vinyl there were stories on the subject from several countries, printed in facsimile (plotting). The visual effect was shocking, but by using newspaper articles I’m also stating the outrage is not only mine, but that it is shared by the majority.

I do not consider myself an influencer, far from it, but I have my opinions and will fight for them.

There’s no such thing as political opportunism. I’m not under or above the law, but I don’t have to condone it. There is no confrontation, no tension, no hostility as well. None of my interferences resulted in uprisings or anything like that. In fact, some of them even got an unexpected ritualistic aspect.

In the one with the crucifix exposing sexual violence, sem-terras (a movement of landless people) were present, people started joining, even if for different reasons, but in a very supportive way.

In fact, there are no disagreements, nor questions that I had to answer for these actions. There are unfavorable criticisms, but as my target audience is not the press, but the interaction of passers-by, the democratization of public events, the criticism are in fact irrelevant.

It’s been ten years since you had a large exhibition in institutional space until this last exhibit in São Paulo, Rio and Paraná. There were some comments stating your artwork is getting closer to the abstraction, or lost a direct relation that previously had with reality. Is this just a vocabulary change, or a quarrel over the eternal struggle between figurative vs. abstractionism, image versus non-image, or what you have shown only has a less identifiable interference at first glance from the realistic standpoint? What has changed?

A less identifiable interference at first glance from the “real” stand point would be a good answer, but it wouldn’t cover enough. Although I am a 100% figurative artist, I do not run away from the abstract language, including the abstract concrete, such as my Bandeira de Caixões (Coffin Flag). My greatest challenge is not only painting but reinventing myself with every work, every painting I create. In this trajectory, everything happened: ruptures, abandonments, returns, reactions, repetitions, corrections, even the destruction of an erroneous work. That’s the real conflict.

Another issue is that smaller individuals (in commercial galleries, not in museums) can’t occur in the same city in a short period of time. For example, the last time I have performed an exhibition in Rio de Janeiro (except the Retrospective which, as the title suggests, was not an unpublished exposition), was ten years ago.

For those who didn’t have the chance to see the exhibitions in Porto Alegre, Belo Horizonte, Curitiba, Recife and, of course, Salvador, which occurred in the meantime, those ten years make a big difference. But even so, those who went to the Objeto Mágico (Magical Object) exhibition will be able to see much of it in this last exhibition, which even features an artwork started back in 1997.

My post-Cesium production (1987) is less “finished” than most of my work from the 1980’s. Currently, it requires more contemplation, there are layers over layers, some thin, others thicker. In the artwork in which are been called abstraction, there are an infinity of figures, if you look closely. The theme is no longer explicit, front and center. Now it covers it all, I think, in a more subtle, less obvious way. Finally, I think art is freedom. Everybody is free to interpret it the way they can or desire.

You are turning 60 now in July, 25. With which artists in art history, from yesterday or from today, do you use as inspiration for your creation today?

I lived in Spain twice and I have always admired the Spanish masters or the ones graduated there, but this is not an exclusivity of mine, because everyone loves the Spanish masters. I visit Europe more frequently than I visit the United States. In general, I like European museums, including the best of the American art, which they also show. Back in 2000, I’ve spent a long period in London. I used to work in Soho, and the National Gallery was practically behind my atelier. I used to go to Tate often and, in my short trips to Paris, I always liked going to the Museum of Natural Science – I was always very interested in anthropology. This is always present in my artwork, such as the O Que Vi pela TV (What I Saw on TV) series, which is all based on rock art.

I also like the work of Tápies, Anish Kapoor, Clemente and many others. However, I confess that although the visual arts are my greatest passion, music occupies a prominent place in my daily life. It would be hard to live without music. I feel that music has more influence over me and we always have the best conversations. Apart from the elementary repertoire, I like some contemporary classics such as Phillip Glass, Thomas Ades, Britten and, above all, Michael Nyman. I’ve been listening to Nyman for years on my atelier. I enjoy cinema very much as well: Godard’s Breathless, and Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin are indispensable. Also, I have always been influenced by “nature” as well. I don’t fool around with nature, I just can’t. Nature is not my theme, but it is one of my greatest guides.

Bahia, a place where you already called your home and atelier, also the city where you won the Primeiro Prêmio Nacional Award, will be included in this exhibition schedule? What would it take for this to happen, to host an exhibition of yours once more?

The exhibition and the book were designed and produced by my southern Brazilian friend Fábio Coutinho. The itinerant exhibition, at first, would happen in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. During the process, D. Maria Estela Requião invited us to include the itinerant exhibition at the MON (Museu Oscar Niemeyer) museum in Curitiba. It lasted almost a year between the three museums. At that time there were no shortage of invitations, but none of them came to happen, which is certainly a shame, because the exhibition was already ready making everything easier. Now, parts of the exhibition have been dismembered. Some of the artwork remains in the museums and others were sold. Surely they could be reunited, but it is indeed a pity that we didn’t do more effort to make it happen. With the artwork still under my auspices, the Museu da Universidade de São João Del Rey invited me to make a “smaller” version of my itinerant exhibition.

It would be a great pleasure to take the itinerant exhibit to Salvador. As you’ve already said, a city with which I have a sincere affinity, open atelier-home, lots of friends, especially Paulo Darzé, who gave me all the support I needed when I used to live there; but the initiative unfortunately cannot come from me. My commitment to art does not allow me to be my own agent. If the MAM-BA didn’t manifest yet it is because they had no interest, and that is unfortunately beyond my reach.

(Interview/July, 2007)